Problems in immediately dismissing an employee with an “on and off” illness

The law protects employees who are absent due to illness from dismissal, if they return to work before the end of the period set down in law. Only a sufficiently long and, in principle, uninterrupted absence due to sickness allows the employer to terminate the contract immediately with an employee who is unfit to work. As a result, situations arise, in practice, in which employees take sick leave “on and off”, interrupting long periods of absence by returning for a few days to work. On the one hand, this is supposed to guarantee further protection against dismissal while, on the other, to ensure that the benefit for being unable to work is received for as long as possible. Nevertheless, it turns out that this strategy will not always prevent the employer from letting the employee go.

Protection during sickness

Accidents (and illnesses) do happen. Anyone who has employees, should be aware of the personal risks involved: members of staff may sometimes temporarily lose the ability to do their job due to ill health. In such a situation, as a rule, labour law protects sick employees, and their employment cannot be terminated by the employer while their “L4” sickness certificate remains valid. This would seem proper: after all, during an illness, one should focus primarily on recovery, rather than worrying about losing one’s job.

Nevertheless, from the employer’s perspective, an employee’s frequent, unforeseen or prolonged absences may seriously disrupt the workflow and require costly organisational measures. The appointment of substitutes, the modification of rosters, hiring additional people for a limited time, assigning overtime work, uncertainty about the success of projects for which the absent employee shared responsibility – these are just some examples of the often-costly consequences of employee absenteeism for the employer. In trying to balance the interests of both parties to the employment, legislators have, therefore, limited the protection against dismissal of an employee who has been absent on illness grounds to a certain period specified in legislation. After the end of this time, the employer may exercise the right under Article 53 § 1 pt 1 of the Labour Code (LC) and terminate the contract with the absent employee immediately.

Immediate no fault termination of employment of an employee absent due to illness

The limits of the period of protection against dismissal depend on the length of service of the individual employee. They are set by Article 53 § 1 pt 1 of LC, which states that an employer may terminate an employment contract without notice (therefore immediately, with effect from when the notice is served to the employee), if the employee’s incapacity to work due to illness persists for:

- more than 3 months – if the employee has been with the given employer for less than 6 months,

- longer than the total period in which remuneration and sickness benefit have been received as well as the first 3 months of rehabilitation benefit – if the employee has been with the employer for at least 6 months or if the incapacity to work was caused by an accident at work or an occupational illness.

Although the duration of protection of an employee with less than 6 months of employment does not raise any real difficulties in interpretation (it is simply 3 months), doubts may arise in if the person has been employed for at least half a year. This is because the Labour Code refers to concepts of social security law, so to fully understand the regulation, we have to refer to the provisions of the law on benefits.

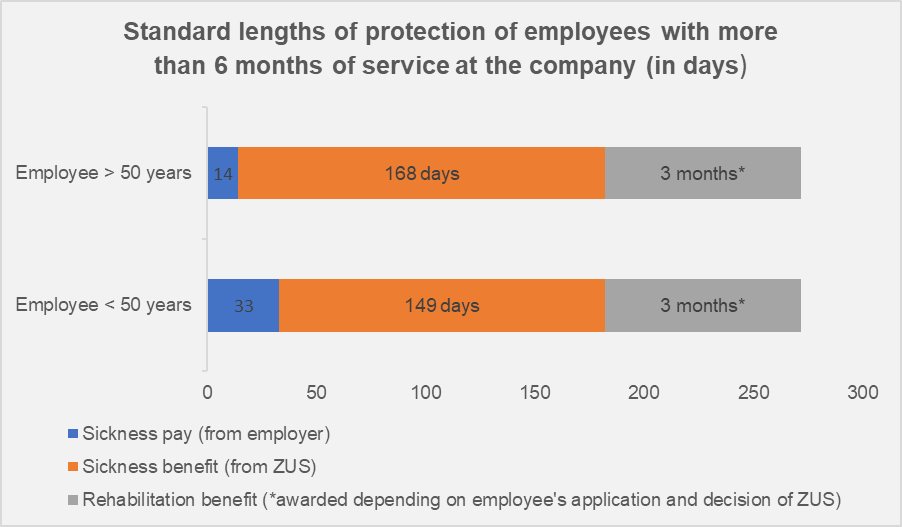

Under those provisions, for the first 182 days of incapacity due to illness (exceptionally, 270 days in the case of tuberculosis or incapacity during pregnancy), the employee is entitled to sickness pay and sickness benefit. The employee receives sickness pay from the employer for up to 33 days (if aged under 50) or 14 days (if aged over 50) in a calendar year. For the remaining period of the mentioned 182 days of incapacity (270 in the case of tuberculosis or incapacity during pregnancy), sickness benefit is payable by the Social Insurance Institution (ZUS). Subsequently, if the incapacity to work persists, the employee may apply for rehabilitation benefit. This is decided by ZUS, after establishing that further treatment or medical rehabilitation are likely to lead to regaining fitness to work. The rehabilitation benefit is given for a maximum of 12 months, but the protection of the sick person’s employment applies to the first 3 months of the benefit, if granted, following the end of the 182 days (270 in the case of tuberculosis or incapacity during pregnancy) of the period of receiving benefit. Only after this time may the employer terminate the contract.

Return to work

Another very important point must be mentioned in discussing the immediate termination of an employment contract of an employee who has been absent for a long time due to illness. Even if the employee has used up the above period of protection, if the employee then recovers and returns to work, the employer then loses the right to this mode of termination. This is because, as Article 53 § 3 of LC stipulates, an employment contract may not be terminated without notice after the employee has appeared at work due to the reason for the absence having ceased.

This provision requires, therefore, two conditions to be jointly met:

- first, the cessation of the reason for the absence due to incapacity to work,

- secondly, the employee’s appearance at work in connection with having recovered fitness to work.

For this reason, neither the mere recovery of the employee’s fitness (not connected with the person appearing at work), nor the mere appearance at work (without recovering fitness to work) takes away the right of the employer to terminate the contract with immediate effect (judgments of the Supreme Court (SC) of 21 May 2014, I PK 290/13; of 29 November 2016, II PK 242/15). It is worth adding that appearance at work is also means the employee starting holiday leave (judgment of SC of 4 April 2000, I PKN 565/99), therefore an in-person return to performing work duties is not even required.

But what about the not-all-too uncommon situation in which, just a few days after returning to work (or immediately after the end of a leave of holiday absence taken right after the employee’s return), the hitherto long-term absentee employee takes sick leave, once again?

Does each return to work “reset” the period of protection?

The mentioned Article 53 § 3 of LC appears quite clear: the employee’s appearance at work, due to the end of the reason for the person’s absence, deprives the employer of the right to summarily terminate the employment contract with that person by invoking the expiry of the period of protection. Supreme Court case law also emphasises that termination of employment in the discussed way requires the absenteeism to last, in principle, continuously (among others, SC judgment of 21 January 2016, III PK 54/15; SC judgment of 19 March 2014, I PK 177/13). Therefore, it is possible to regard taking “on and off” sick leave as enabling the “reset” of periods of protection and protecting the employee effectively against termination of employment for a further pool of 182 days of the duration of benefit and then a further possible 3 months of rehabilitation benefit.

However, the situation may be liable to change due to an amendment, introduced at the start of 2022, to the provisions of the law on benefits. In the previous legal state, only a repeated incapacity to work due to the same illness could be included in the previous period of benefit. Therefore if, following a return to work for a few days, the employee secured an “L4” sickness certificate due to the onset of a different illness, the employee thus gained an entitlement to a new full period of benefit, and then also possibly rehabilitation benefit. Currently, periods of previous incapacity are included in the period of benefit (the “same illness” requirement does not apply), if the interval between the end of the previous and the onset of the new incapacity to work has not exceeded 60 days – unless the “new” absence has arisen during pregnancy. In simplest terms, therefore, the current entitlement to a new pool of benefits for a temporary incapacity to work (other than during pregnancy) does not arise until the 61st day after the end of the previous incapacity.

This somewhat complicated scheme is best illustrated by the following example:

| In January, an employee contracted illness X and lost the ability to work. For the first 182 days he received sick pay from his employer and then subsequently sickness benefit. Immediately after this, he gained an entitlement to four months of rehabilitation benefit. The employee informed the employer that he would like to take holiday leave immediately after his rehabilitation benefit ended, to which the employer agreed. In November, the employee underwent a medical examination which found him fit for work and was subsequently granted a week’s leave of absence, as requested. Nevertheless, he failed to turn up for work: on the day of his planned return, the employee informed the employer that he was holding an “L4” medical certificate due to another illness. |

If the described situation had occurred before 2022, the employee would have been entitled to another full period of benefit due to the new illness. The employer would have therefore undeniably lost the right to terminate the employee’s contract with immediate effect for no fault of the employee until the new period of protection had ended.

However, in the current state of the law (since 2022), the employee does not become immediately entitled to another period of benefit. Since only one week has passed between the end of one incapacity and the onset of the second (which has not occurred during pregnancy), the new period of benefit may only start after the end of a further 53 days, so that the break would total at least 60 days.

Nevertheless, may the employer terminate the employee’s contract of employment during this period with immediate effect for no fault of the employee, in view of the provisions of the law on benefits which imply that a new period of protection will apply only 60 days after the end of the previous one?

Such an interpretation would be justified, given the strong correlation of the Labour Code with the provisions of the law on benefits (the Code uses, among others things, concepts from this law such as “remuneration and sickness benefit”, “rehabilitation benefit”). Nonetheless, as already mentioned, Article 53 § 2 of LC accentuates the requirement of an uninterrupted absence, stipulating that the employer may not terminate the employment contract with immediate effect for no fault of the employee after the employee has appeared at work, due to the cessation of the reason for the absence.

From the lists of court cases

Recently, the courts in Łódź faced exactly this issue, in a case similar to the above example. They were considering an appeal of a long-term absentee whose employment contract had been terminated with immediate effect for no fault on her part.

The district court had agreed with the employee, holding that, having returned to work for several days between the end of one sickness absence and the start of the next, she was entitled anew to a full period of protection (despite having fully taken her period of benefit). Therefore, by terminating the contract, the employer had breached the law, and the employee was entitled to compensation.

| The period of protection lasts while the employee is continuously absent from work, and it is irrelevant whether it has one cause or many (the same illness or a different one). What is important, however, is that these periods form an uninterrupted whole. This is because any break between consecutive periods of incapacity to work causes a period of protection to start anew. This period begins with the first day of absence and ends with the day on which the employee reports for work due to the reason for the absence having ceased. Once the employee reports for work, the employer loses the entitlement under Article 53 of LC; the employer may then terminate the employment contract only under general rules. Judgment of the District Court for Łódź-Śródmieście in Łódź of 29 December 2022, X P 309/22, quoting from the grounds of the judgment of the Regional Court |

However, the regional court hearing the case at the second instance made a different interpretation. It agreed with the appealing employer that the provisions of the Labour Code should be interpreted in close conjunction with the law on benefits. Therefore, since, in accordance with the law on benefits, the employee had used up her entire period of benefit and had not yet acquired the right to a further period of benefit, her brief return to work did not preclude the termination of her contract with immediate effect for no fault on her part.

| (...) Based on the previous state of the law, in regaining her fitness to work on 31 December 2021, which was adjudicated previously with illness code F43 – reaction to severe stress and adaptive disorders – and then taking sick leave from 19 January 2022 with illness code J06, the claimant would start benefiting from a new period of benefit (a break of less than 60 days, but different illness codes), and the employer would not be entitled to terminate her contract without giving notice. (...) It follows from the current wording of Article 9 par. 2 of the Act on Social Insurance Cash Benefits in Sickness and Maternity that any subsequent incapacity to work arising after an interruption not exceeding 60 days, regardless of whether due to the same or a different illness, is included in a single period of benefit. (...) As the claimant was absent again from work due to illness from 19 January 2022, and 60 days had not elapsed since the end of the previous incapacity, the employer was entitled to treat this period as continuous and cumulative based on the current wording of Article 9 par. 2 of the law on benefits. Judgment of the Regional Court in Łódź of 24 May 2023, VIII Pa 12/23 |

In our view, the Regional Court’s line of interpretation is more convincing. This is because, first of all, the purpose of Article 53 § 1 of LC is to protect the employer from having to continue to employ a person who is incapable of performing employment duties for a long period of time. If it is accepted that a break of even just a few days between long periods of absence can “reset” the period of protection and extend it significantly beyond the period of the benefit, this could therefore lead to the employer suffering unjustifiable harm. Secondly, since under the Labour Code for a large proportion of employees the length of the period of protection is closely linked to the period of benefit, it is unclear how one should compute the protection period of an employee who has expended this period of benefit. Therefore, we endorse the position in which, although in accordance with Article 53 § 3 of the Labour Code, an employment contract cannot be terminated without notice after the employee has reported for work due to the cessation of the reason for the absence, if the employee becomes incapacitated before the period of benefit has been renewed, immediate termination should be regarded as acceptable.

Summary

The interpretation of Article 53 § 1 pt 1 of LC on terminating employment contracts with immediate effect due to an employee’s long-term absence on sick leave causes problems, mainly due to its ties to the far-from-simple provisions of the law on benefits. The situation has been further complicated by the recent change in the rules for acquiring the right to successive periods of benefit.

The 60-day interval, which legislators have passed, between the end of the previous incapacity to work and the emergence of a new incapacity (regardless of whether caused by the same or a different illness) was primarily intended to prevent abuses and situations in which a right to a new period of benefit arose without the need to undertake any work. As the Łódź Regional Court stated in the recent judgment, it seems that this change has indirectly strengthened the position of employers seeking to part ways with employees suffering from “on and off” illnesses. Time (and further court judgments dealing with the problem) will show whether jurisprudence will follow this line of interpretation.

Meanwhile, it is invariably advisable to be particularly cautious when terminating the employment of a long-term absentee employee: checking carefully the employee’s periods of absenteeism and comparing them with the protection periods under Article 53 § 1 pt 1 of LC.

We also encourage you to read our article on frequent absenteeism as a reason for terminating the employment contract.

Marcin Wujczyk

Krzysztof Jajor